Gift cards are a favorite way for scammers to squeeze money out of their victims. Unlike wire or bank transfers, where the bank or the transfer service tracks the transaction and may have fraud protection in place, the only information needed to redeem the value of a gift card is the alphanumeric code on the back, which can be sent via email or read out over the telephone. Once scammers have the code, they can then sell it on at a discount, converting it into their local currency without any sort of paper trail linking them to either the gift card or their victims, and without any pesky banks (and their anti-fraud measures) looking over their shoulders.

While a lot of retailers and companies that use gift cards have taken measures to limit the damage that scammers can do – capping the maximum amount you can buy in a day, for instance – the simple fact is that what makes these types of cards useful is exactly what makes them attractive to scammers. They’re as good as cash to anyone who wants to buy something from the company that issues the card, and they can be “sent” instantly and without a trace anywhere in the world in seconds.

Some scams are fairly elaborate and require a high degree of involvement from scammers. Tax authority scams – telling targets that they owe money to the Internal Revenue Service (or some equivalent agency) and must immediately pay off the debt or go to jail – often involves scammers staying on the phone with their targets for an hour or more, walking them through the process of buying a gift card and transferring the code to them. Tech support scams require scammers to be able to convince targets to install remote administration software on their computer, and then convince them to buy a gift card.

And then there are the scammers who take the easy approach: they just ask. Typically, this ask happens via email, where the scammer will pose as the targets’ boss or an official in their company, and claim to have an urgent need for gift cards. While on a victim-by-victim basis this is probably less lucrative than tax scams or ransoming a target’s computer back to them, it makes up for it in speed and simplicity. Scammers can send as many emails as they like, and they only need to get lucky once to net a nice payday.

Anatomy of a Business Email Compromise (BEC) gift card scam

While the exact details vary per scam, the steps often follow this general pattern:

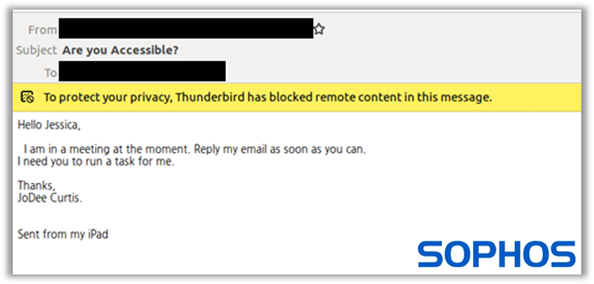

1. The contact – scammers will email a number of targets, usually with a very short message like, “Are you there?” or “Are you available right now?” Occasionally, they’ll step up the urgency with a subject line like, “Please respond!!!” This is because the scam relies on getting money out of targets before they’ve had a chance to think about it and realize they’re being scammed. Scammers are looking for and depending upon people who will quickly or reflexively respond to a person of authority demanding an action.

2. The ask – once targets are “qualified,” by responding quickly to the request, scammers will then demand the gift cards. They’ll make up a reason that a) they need gift cards and b) they can’t do it themselves (in a meeting, stuck in traffic, etc). If they haven’t cranked up the urgency yet, this is where it happens: “I need this ASAP” or “This is super important, please let me know how fast you can get to this.”

3. The attack – once targets have agreed to get the gift cards, scammers send over details, including the specific type of cards to buy, denominations, and instructions to pay out of pocket and then expense it or to pay in the most expedient way possible. Scammers usually re-emphasize urgency here, by stating how important the “ask” is to the company and how fast they need the job done.

4. The loot – once targets have the gift cards in hand, scammers will ramp up the urgency one last time, telling them that the matter has become even more urgent, and they should just send the codes off the back. Once targets do this, the scam is over, and likely the last time scammers contact them.

How SophosAI stops BEC scams

Sophos has taken a combination of state-of-the-art Natural Language Processing (NLP) models and hand-designed features to produce a high-performance BEC detection system. Our CATBert (Context-Aware Tiny Bert) model is based on the Transformer architecture, the same NLP architecture that powers such efforts as Google’s search tools. The key innovation behind the Transformer is the introduction of self-attention heads: sub-modules of the network which learn to understand words in context rather than individually, and extract much more nuance from a chunk of text than simpler models, including notions like “urgency” and “asking for something.” We’ve further augmented these self-attention heads with some additional features that are specific to email – including whether or not the sender and receiver share the same domain, the size of the recipient list, and the number of people in the CC field – in order to efficiently detect BEC scams, including gift card ones.

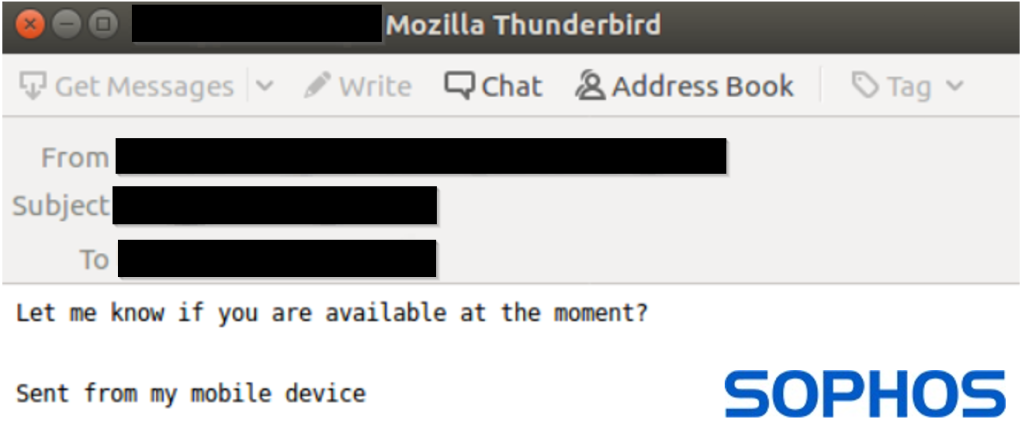

Despite its short length, the initial “contact” email below was caught by SophosAI’s system and assigned a score of “likely malicious.” It contains all the hallmarks of a targeted BEC campaign: an external email address with a display name of a high level company executive and a “high-urgency” subject line with a body requesting immediate response.

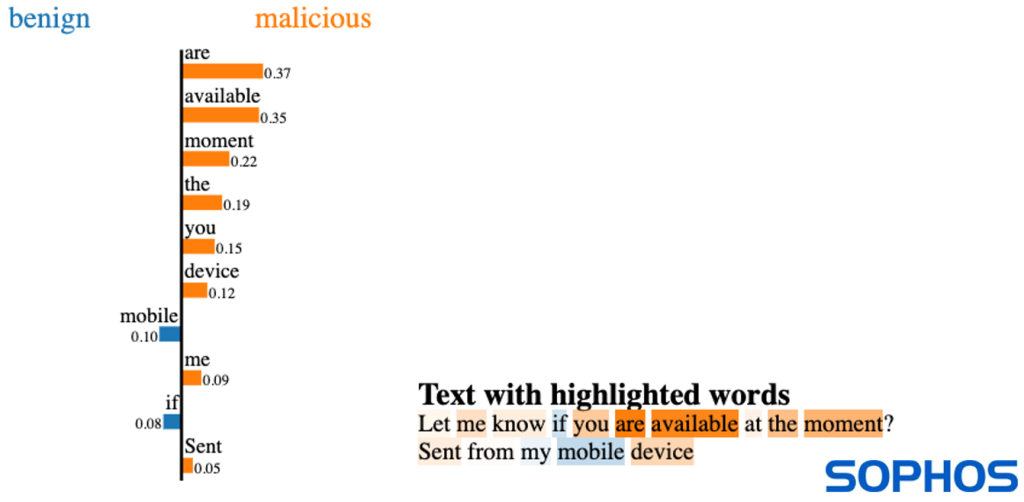

While inferring things like urgency and tone directly from the model analysis is difficult, we can use a technique called LIME to inspect what the model found most informative about the text of this particular email when it came to making a decision about whether or not it was phishing. Here we can see that the model has picked out the sequence “…are available [at] the moment…” as being highly indicative of a malicious email, so it seems likely that the model has keyed in on “sense of urgency” combined with the email originating from an external domain as a key indication of maliciousness. It’s worth noting that we didn’t have to train the model to detect “urgency” – by using the transformer architecture combined with a number of examples of phishing emails, the CATBERT model can identify the concept of “urgency” on its own and learn to link that with phishing emails.

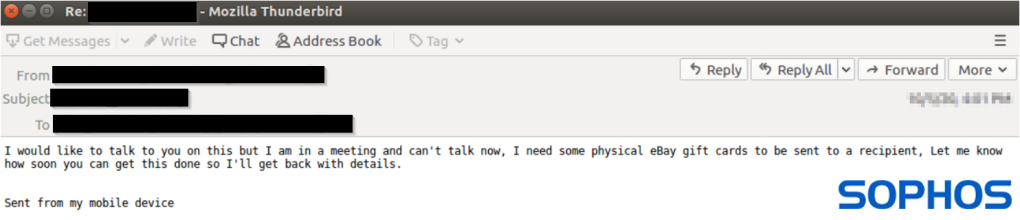

Unfortunately, in this case, the target responded to the email, prompting an immediate follow-up in the form of an “ask” email, which our machine learning (ML) model again scored as “likely malicious.” And again, all the classic elements of the “ask” phase of a BEC attack are in place: a request for gift cards, an excuse for why they can’t talk on the phone, and an emphasis on speed and urgency. At this point, the scam was interrupted, and the attack stopped.

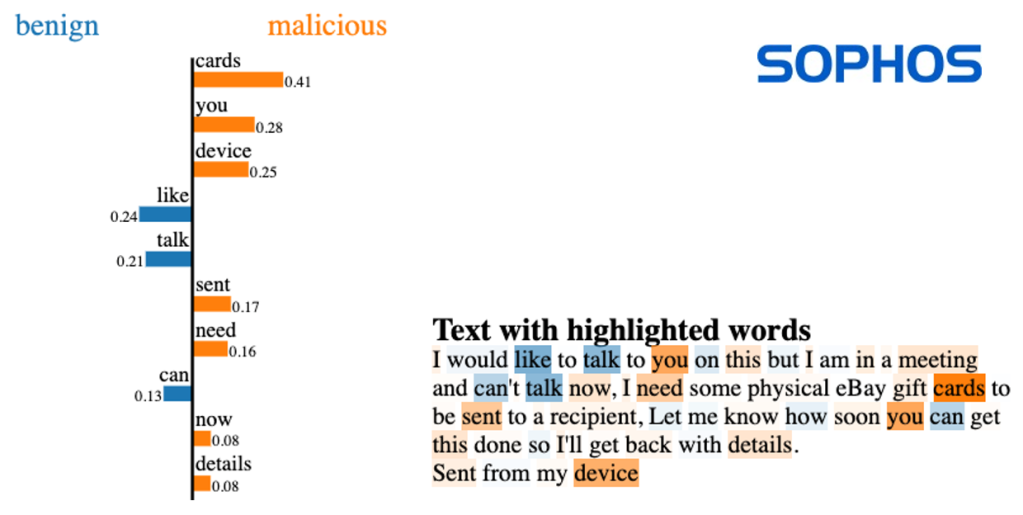

Once again, we can investigate the LIME outputs of the model and see that in this case, the word “cards,” particularly in conjunction with “need,” set off alarm bells for the model. What is interesting is that in a completely different context (for instance, “please sign the birthday cards in the break room”) the word “card” has almost no loading for malicious or benign either way. This is the power of self-attention – the model can evaluate the word “card” in the context of the full email and our email-specific features to be able to classify it as a phishing email.

Hopefully, this example of our models in action piqued your interest a little bit. If you want to learn more about how our ML models can detect and help interrupt this sort of attack, check out our previous post on the topic, or our talk at the DEF CON AI Village.