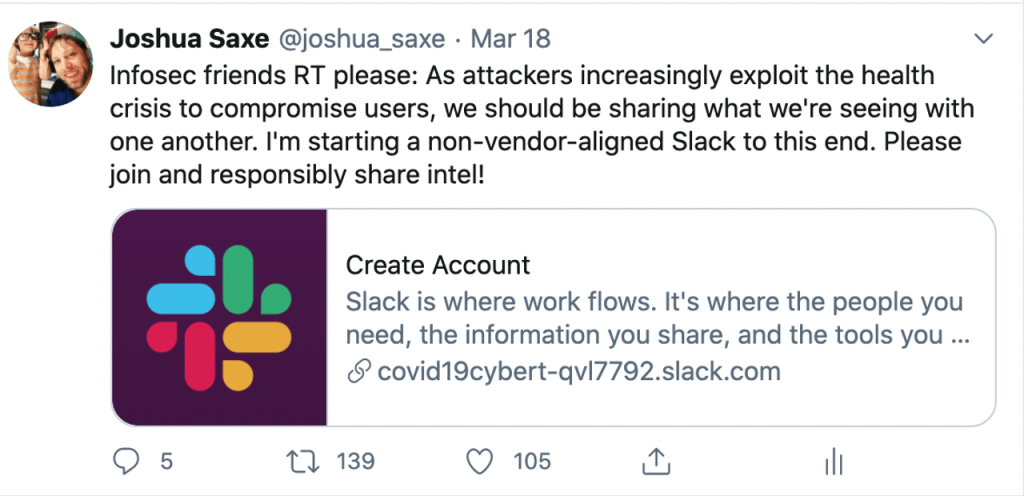

When I posted this tweet in March of this year, kicking off a process which would give birth to the Covid19 Cyber Threat Coalition (CCTC), I assumed no one would respond. Four months later, the CCTC has more than four thousand participants, has received international news coverage, has garnered the participation of global law enforcement organizations, cybersecurity vendors, IT security departments, and mutual defense organizations, and, most importantly, has stood up infrastructure that has protected users from cyber-attacks millions of times. As a broad group of volunteers including many members of the Sophos AI team, we’re building an enduring “commons” for the community to leverage in times of crisis, and we’re close to achieving not-for-profit status under the auspices of a mature consortium of vendors, the Cyber Threat Alliance.

How we got from there to here, what lessons we learned, what we accomplished, and how we’re now proceeding is the subject of this blog post.

The structure of the Covid19 Cyber Threat Coalition (CCTC)

A guiding principle for the leaders of the CCTC has been simplicity, and our organizational structure reflects that. The CCTC has a steering committee, comprised of individuals who head up individual areas of work (publicity, threat intelligence infrastructure, program management, data science, our threat advisory work, community building, and outreach). Outside of the steering committee, we have core volunteers in each of these areas. We also have a broad pool of participants in our Slack who utilize Slack and Alienvault Open Threat Exchange to exchange threat information. We plan to stick to this structure (steering committee, core volunteers, and participating volunteers) as we go forward.

In line with the simplicity maxim, we’ve sought to define our scope simply. We’re focused on publishing blocklists of malicious URLs and domains for ingestion into vendors’ product blocklists and into organizations’ endpoint and network security technology ecosystems as our core mission. We’re not focused on takedowns of malicious actors, although the law enforcement organizations who participate in CCTC do use our blocklists to this end. And we’re not focused on detailed profiling of criminal organizations, although we do have members who use our blocklists as inputs into their deep threat intelligence work.

We’ve found that the scope I’ve described works well in an all-volunteer context. Volunteers only have so much time they can dedicate and come and go as priorities change in their personal and professional lives. By focusing on low-bandwidth activities like identifying and disseminating malicious domains and URLs, we can leverage thousands of low-bandwidth volunteers in productive ways.

What we’ve accomplished and where we’ve faced challenges

As I wrote above, the crown jewel of the CCTC’s accomplishments are its pipeline for gathering and disseminating information about malicious URL and domain indicators of compromise (IoCs). This works as follows. Hundreds of volunteers submit indicators to Alienvault Open Threat Exchange, which is a free-to-use threat intelligence platform whose creators are members of CCTC.

These indicators are then snatched up by the ThreatConnect indicator processing (SOAR) platform and tested to make sure they’re still active and are not false positives. Then, software we’ve written running in a cloud virtual machine pulls these indicators from ThreatConnect and posts them to an HTTP-accessible blocklist we have posted at http://blocklist.cyberthreatcoalition.org. This process is continuous, and our blocklist is updated every 10 minutes. We post many thousands of new indicators a day, and our blocklist is utilized by government agencies, law enforcement, hospital networks, security vendors, threat exchange platforms, and IT security departments all over the world.

Beyond merely standing up this pipeline, a key strategy we’ve pursued has been to actively solicit other blocklist disseminators to adopt our blocklist. We’ve succeeded in getting major security vendors to vet, validate, and adopt our blocklist, and this has led to massive amplification of our work. For example, the free secure DNS provider Quad9 has adopted our blocklist, and its led to more than 10 million block actions in which users attempted to load malicious content and Quad9 blocked them from getting compromised, thanks to our joint efforts.

Challenges and lessons

Building CCTC has not been without challenges. The first challenge we faced was in creating an organizational structure from scratch out of hundreds of interested volunteers all of whom had limited time and many of whom were dealing with their own personal and professional crises as Covid-19 developed as a major health and economic crisis. We struggled to find an organizational structure that worked, and to manage chaos. Our effective response was to remain open to radical revisions of our organizational structure over the first two months of the life of our nascent effort. By the end of the second month, we had a stable mission and structure in place, but it took precious time to get there.

A second, related challenge we faced was the problem of achieving professional results in terms of defending the public with an army of volunteers that we don’t pay and who can’t prioritize their volunteerism over their paid-professional and family commitments. Our response was to narrow our scope such that it’s suited to a volunteerist environment. Publishing a blocklist fit the bill here, as did the work of building our Slack community, publishing a weekly threat advisory, and hosting virtual-conference style Town Hall meetings with external speakers. Had we focused on higher-commitment activities like cyber-criminal law enforcement takedowns, I believe we would haven’t achieved such excellent results.

Where we go from here

Had we had the social infrastructure of the organization we’ve built, the technical infrastructure we use to collect and disseminate threat intel, and the “amplifier” relationships we’ve built with downstream organizations like Quad9 and major security vendors at the beginning of the Covid-19 crisis, we would have had an even greater impact in protecting the public. Fortunately, we have these durable accomplishments under our belt now. The next time volunteers become willing to step up to help address a crisis, we’ll be able to hit the ground running thanks to the work we did this year.

To ensure this is indeed the case we plan to work on making the Covid19 Cyber Threat Coalition a permanent, institutional “crisis commons” for our community. This involves getting not-for-profit status as a surrogate of the established vendor coalition, the Cyber Threat Alliance, and firming up donor relationships with companies like Slack, Atlassian, Google, ThreatConnect and others who have donated SaaS technologies that have enabled our achievements. We’ll be doing this while continuing our Covid19 activities and continuing to address the evolving cybercrime wave we anticipate in response to the evolving global economic recession.

How to get involved

If you’ve read this far, thank you for your interest in our work. Here at Sophos AI, we believe that doing community service work, such as participating in the CCTC, is a vital part of what it means to be a researcher within the cybersecurity community. If you’d like to get involved, please go to our website, https://www.cyberthreatcoalition.org/ for information on how to join our Slack. If you’d like to become a core volunteer, please DM me on Slack, and I’ll start the process of getting you set up. We’ve come a long way in building the foundation of what we hope will become a key institution in our professional community’s ability to respond to cybersecurity crises, but it will take more volunteer time and energy for us to move forward.